Cognitive decline and impaired memory in aged individuals, often referred as “dementia”, have been recognized for a very long time. One of the earliest references to age-related mental deficiency is attributed to Pythagoras, the Greek physician of the 7th century B.C.

Pythagoras divided the life cycle into five distinct stages, commencing respectively at ages 7, 21, 49, 63, and 81, the last two of which were designated the senium, or “old age”—a period of decline and decay of the human body and regression of mental capacities.

However, it was not until 1906 that a German psychiatrist, Alois Alzheimer, identified and carefully described the first case in his patient, Auguste Deter, a woman in her 50’s who developed memory, language, and orientation problems as well as delusional thinking.

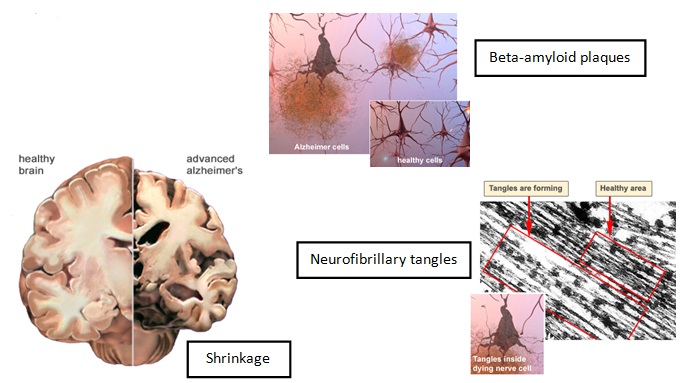

Upon Auguste’s death, Dr. Alzheimer autopsied her brain, and found a: “dramatic brain shrinkage and abnormal deposits in and around nerve cells.”

Today we know that these deposits “in and around nerve cells” are the two hallmark pathological signatures of Alzheimer’s disease, namely amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles.

In 1910, Dr. Emil Kraepelin, who worked with Dr. Alzheimer, named the disease after his mentor.

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia, accounting for an estimated 70% of cases. AD is an irreversible and progressive brain disease, with the most common early symptoms being memory difficulties and trouble learning new information.

In general there are three main stages in the development and progression of the disease:

- Pre-clinical or pre-symptomatic phase: The silent stage during which protein aggregates (amyloid plaques and tau fibrillary tangles) are accumulating in the brain, but are insufficient to cause noticeable symptoms.

- Mild Cognitive Impairment: Symptoms become noticeable to the affected individual and/or family and impairment start to be significant but does not interfere with everyday activities.

- Alzheimer’s disease: Significant loss of intellectual ability occurs, affecting memory plus one or more other cognitive ability, and the impairment interferes with everyday functioning.

Today, AD is recognized as the primary cause of cognitive impairment in older adults. An estimated 5.5 million Americans of all ages are living with AD.

According to the Alzheimer’s Association’s 2017 Alzheimer’s disease Facts and Figures:

- 1 in 10 people age 65 and older has AD

- 1 in 3 seniors dies with AD or another dementia

- AD is the 6th leading cause of death in the United States

- 2 in 3 Americans with AD are women

- More than 15 million Americans provide unpaid care for people with AD

- In 2017, AD will cost the nation $259 billion, and costs are expected to exceed $1 trillion by 2050

Symptoms

The most common early symptom of AD is difficulty remembering newly learned information because Alzheimer's changes typically begin in the part of the brain that affects learning and memory. As the disease advances through the brain it leads to increasingly severe symptoms, including disorientation, mood and behavior changes; confusion about events, time and place; unfounded suspicions about family, friends and professional caregivers; more serious memory loss and behavior changes; and difficulty speaking, swallowing and walking.

Diagnosis

AD is diagnosed through a complete medical assessment. If you or a loved one have concerns about memory loss or other symptoms of AD or dementia, it is important to be evaluated by a physician.

There is no single test that shows a person has the disease. While physicians can almost always determine if a person has dementia, it may be difficult to determine the exact cause. Diagnosing AD requires careful medical evaluation, including:

- A thorough medical history

- Mental status and mood testing

- A physical and neurological exam

- Tests (such as blood tests and brain imaging) to rule out other causes of dementia-like symptoms

Having trouble with memory does not mean you have AD. Many health issues can cause problems with memory and thinking. When dementia-like symptoms are caused by treatable conditions — such as depression, drug interactions, thyroid gland problems, excess use of alcohol or certain vitamin deficiencies — they may be completely reversed.

Treatment

Currently, there is no cure for AD. However, some drug and non-drug treatments may help with both cognitive and behavioral symptoms. All of the prescription medications currently approved to treat AD symptoms in early to moderate stages are from a class of drugs called cholinesterase inhibitors. Cholinesterase inhibitors (Aricept, Exelon, Razadyne) , which help increasing the levels of acetylcholine in the brains, are prescribed to treat symptoms related to memory, thinking, language, judgment and other thought processes.

Another drug approved for AD is memantine (Namenda), which regulates the activity of glutamate, a chemical involved in information processing, storage and retrieval, can also help combating symptoms related to memory, thinking, language, judgment and other thought processes. Memantine can be used alone or with other AD treatments. There is some evidence that individuals with moderate to severe AD who are taking a cholinesterase inhibitor might benefit by also taking memantine. A medication that combines memantine and a cholinesterase inhibitor is available (Namzaric).

Researchers are looking for new treatments to alter the course of the disease and improve the quality of life for people with dementia. As a result, today, there is a worldwide effort under way to find better ways to treat the disease, delay its onset, and prevent it from developing.

Brain Changes

We do not yet fully understand what causes AD, but it is clear that it develops as the result of a complex series of events that take place in the brain over a long period of time. Essentially, every person with AD has accumulations of amyloid plaques (comprised of the toxic beta-amyloid protein) and neurofibrillary tangles (aggregates of the tau protein) in the brain.

The abnormal accumulation of plaques and tangles cause neuron cells to die, leading to dramatic shrinkage and cell loss affecting areas of the brain that are responsible for memories, thoughts, emotions, movements, and skills.

Scientists are conducting studies to learn more about plaques, tangles, and other features of AD. Today new technology has made it possible to visualize plaques and tangles by imaging the brains of living individuals.

Findings from these studies may help researchers and clinicians better understand the causes of AD. It is likely that the causes include genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors.

Genetics

From a clinical point of view, AD can be divided into two major forms: early AD and late onset AD. Familial Alzheimer's disease, or early-onset AD, is inherited and rare. It affects less than 4 percent of all AD patients. It develops before age 65, in people as young as 35. It is caused by gene mutations, or permanent changes in the DNA of chromosomes 1, 14, or 21. If even one of these mutated genes is inherited from a parent, the person will almost always develop AD. All offspring in the same generation have a 50/50 chance of developing this type of AD if one parent has it.

However, the majority of AD cases are “late-onset AD”, usually developing after age 65. Late-onset AD has no known cause and shows no obvious inheritance pattern. However, in some families, clusters of cases are seen. Although a specific gene has not been identified as the cause of late-onset AD, some genetic factors do appear to play a role in the development of this form of the disease. A gene called Apolipoprotein E (APOE) appears to be a strong risk factor for the late-onset form of AD. The APOE gene has three forms: APOE e2, APOE e3, and APOE e4. Carrying one or two copies of APOE e4 increases a person’s risk of getting AD. Carrying APOE e4, however, does not necessarily mean that a person will develop the disease. However, also people who carry only APOE e2 and/or e3 can and do develop AD.

Large-scale genetic research studies are searching for other genes that increase or decrease susceptibility to AD.

Lifestyle Factors

A nutritious diet, exercise, social engagement, and mentally stimulating pursuits can all help people stay healthy. New research suggests that such healthy lifestyle choice also might reduce the risk of cognitive decline and AD. Scientists are investigating associations between cognitive decline and heart disease, high blood pressure, cholesterol, diabetes, and obesity, as well as lifestyle practices. Understanding these relationships and testing them in clinical trials will help clarify the extent to which controlling chronic health conditions and adopting healthy lifestyle practices may lessen the incidence of AD.