From White Coats to Cadavers: Temple’s Newest Medical Students Earn Their Rites of Passage

By Michael Vitez | August 12, 2016

This is a story in two parts.

Friday:

Glen Martin’s dad was standing in the back of Temple University’s performing arts center, giant zoom lens at the ready. This was a moment he did not want to miss.

His son decided in high school to become a doctor, after taking a hit as soccer goalie and being airlifted to a Boston hospital.

“Fourteen hours of surgery kept him alive,” said the father, Melvin Martin. “And he’s here.”

The son, so influenced by the life-saving experience, was one of 206 students at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine’s White Coat Ceremony.

This is the moment when medical students put on for the first time their white coats, symbolizing the beginning of their medical education and journey to becoming physicians.

A thousand family members and friends filled the hall, tears flowing, videos rolling, necks craning to see.

Nokulunga Luthuli, a mother from Pittsburgh, leaned over the railing, as her son, Keith Luthuli, was helped on with his coat by Dr. Larry R. Kaiser, dean of the medical school.

Tears filled her eyes.

“Believe me,” she said, “it took a lot to get here.”

For her son and for herself.

“I’m a single parent of four,” she said. “It was a hard journey, a lot of sacrifices to help him out.”

The first time her son applied, he was rejected.

So he studied harder. Tried again.

“I’m very proud, so proud,” she said. “He never gave up his dream.”

The future physicians came from 25 states; 30 were foreign born, from Kazakhstan and Kenya and Korea and Kuwait and so many others. Half were women; eighteen percent minorities. There was a financial analyst and a first violinist, a ski instructor and school teacher and opera singer.

Silpa Tadavarthy from Mechanicsburg, PA had 12 family members come from as far as Boston and Minneapolis to celebrate the moment. She was born with albinism, a genetic condition that impairs her vision, and needs a variety of assistive devices to study and learn. But her passion to be a physician burns no less brightly. “She did not give up,” said her mother, Jyothi.

“From the moment you put on that white coat this morning,” Dr. Kaiser told the students, “you become part of a great and revered profession.”

“You must learn to see the world as your patients do,” he added. “It all begins with that … a personal connection with the patient.”

“Medicine is both science and art,” Dr. Kaiser concluded. “It is lifelong learning. It is education without end… To patients it is hope and healing.”

“We will expect a lot from you. We will invest a lot in you.”

Off they went to celebrate with families, enjoy the weekend.

Anatomy lab would start Monday.

Monday:

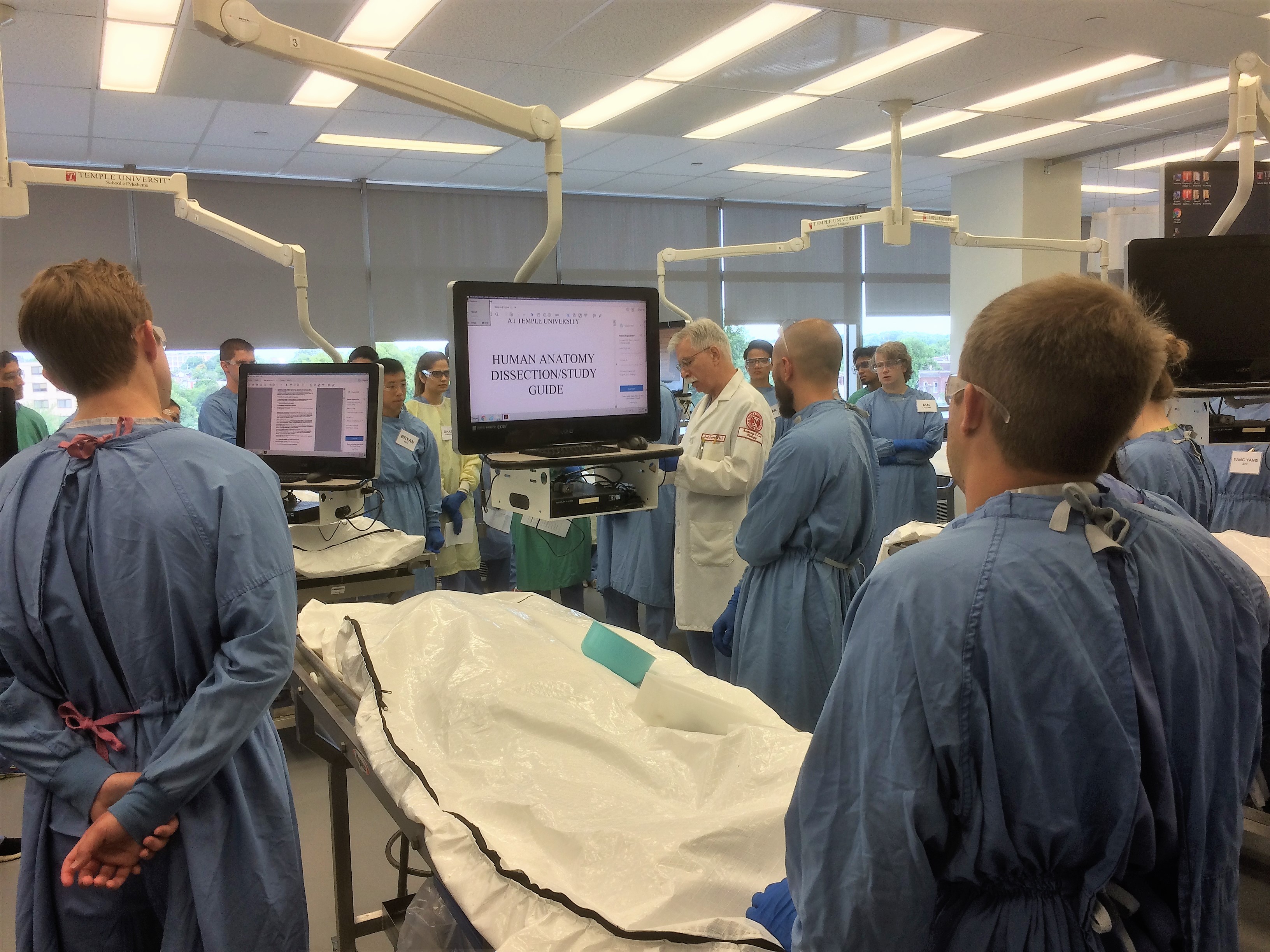

At 9 a.m. scrubs and gloves replaced the suits and ties. Stained glass had given way to stainless steel tables.

They unzipped the body bags, met their cadavers, which were shades of gray from the preservative, face down, heads still wrapped. The room was sterile, clinical, professional.

The backs of the cadavers had been cut open during the preservation process, and sewn shut. The students begin by untying the string, peeling back the skin, and seeing what was beneath. For the most part, they simply got to work. They picked up the spine, or felt for muscles, ligaments, nerves. Their gloved hands explored the human flesh and bone.

It was a privilege to observe these first moments, to hear their comments.

A sampling:

“It wasn’t really real to me until I saw the hands.”

“This was a life. This was somebody’s body that moved them through their life.”

“I feel like he’s our friend.”

“So once we get the trapezius up, we do the rhomboids, right?”

(With every cadaver was a computer screen filed with diagrams and questions, such as: “What are the bony landmarks that are palpated to help locate the spinous processes of the C7, T3, T7, L4 and S2 vertebrae?”)

“I feel like I’m reacting more to the pace than anything else. We have eight pages of the material to get through today.”

“It’s intimidating. The speed of it is intimidating.”

“My grandmother is older and in a nursing home and she has wrinkly skin and she’s about this size. So it’s pretty emotional to realize this is a person.”

“I haven’t touched it yet. I’m kind of scared. I’m not going to lie. I’ll do it later. Ease into it.” A half hour later, as her hands probed the muscle and fascia: “I was tentative but then I did it and now I’m ok. It’s cold. It doesn’t feel like a person.”

“I’m exposing the dorsal scapular nerve.”

“I was watching the Olympics last night,” said one, holding up and marveling at the backbone. “I wonder if Simone Biles’ spine is different than ours?”

Michael Vitez, winner of the 1997 Pulitzer Prize for Explanatory Journalism at The Philadelphia Inquirer, is the director of narrative medicine at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University. Michael.vitez@temple.edu