White Coat Reflections

All second year students at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine recently were asked to write reflections on wearing their white coat. Within a few weeks they would be wearing them every day, beginning their third year of medical school and rotations in the hospital caring for patients. They were asked to reflect on what wearing their white coat meant to them. The following six essays were chosen by the Narrative Medicine team to be read at a ceremony marking the transition.

Lauren D’Andrea

Imposter

Lauren D’Andrea

I put on a white coat for the first time almost 2 years ago with excitement, proud to wear a nearly universal symbol of intelligence, healing, compassion, respect. But as classes got underway, I quickly began to doubt my right to wear such a powerful symbol. Medical coursework challenged me and caused me to often question whether I was truly capable of learning, remembering, and applying such a broad base of knowledge. I felt like I was going through the motions, showing up to class, learning how to perform a physical exam, passing the tests. But I constantly worried that I wasn’t smart enough. The term for this, as you may be aware, is “imposter syndrome.”

I recently re-read an article that I had stumbled across at the beginning of medical school. I found that it resonated with me even more strongly now than it had in those first few weeks. It’s titled “Letter to a Young Female Physician”, written by Dr. Suzanne Koven. She talks openly about her struggles with imposter syndrome, saying, “You see, I’ve been haunted at every step of my career by the fear that I am a fraud.” I believe this sensation is familiar to many medical students. But the danger of this feeling is that it convinces you that you are experiencing imposter syndrome more than others, that others can’t fully relate. You’re hesitant to discuss it too much with others, because you simultaneously want validation and are terrified that someone will discover that you are, in fact, an imposter.

I’ve spent the past 2 years waiting for this sensation to subside. I’ve used every passing grade and every positive comment from my mentors to tell myself, “See! You’re making it!” I keep telling myself, well, if I pass this test, then I’ll know I’m really capable. I’ve looked to close friends and family for validation — validation of my doubts as well as the fact that I should not doubt myself; that this fear is wrong. Everyone is quick to assure me it’s normal to feel this way, that I do in fact belong. But the little voice in my head, the little pit of doubt, never goes away.

Ultimately, I’ve realized two things. First, the validation I seek so desperately has to come from myself. Since my doubt in my abilities only comes from myself, I can only fight it myself. Secondly, I have to accept that I will may never be rid of this feeling completely. This is not going to be a one-time, convince-myself-I’m-smart epiphany, after which I no longer no doubt myself. I will likely feel some level of imposter syndrome, on and off, throughout my training. Instead of waiting for it to go away, perhaps I need to focus on forging ahead despite this feeling. To prove the little voice in my head wrong. To excel despite my fears that I will fail.

So, what does a white coat mean to me? It means a challenge. It means a level of respect that I have to strive towards. The white coat was handed to me, but I have to earn it. I have to believe that I deserve it. And I have to celebrate my strengths. Because those strengths that cannot be taught, tested, measured, objectively assessed — those are the skills that will ultimately help heal my patients. Not my ability to memorize every cytokine and drug mechanism of action and biochemical pathway that I will likely never use in my practice. But my ability to listen, to empathize, to connect, to comfort.

Those skills are what make me feel I deserve to wear this white coat. Those are the skills that prove that I am not, in fact, an imposter. That I am, despite all my doubts, smart enough. I am strong enough. I am enough.

Azam Husain

The Whitest White Coat

Azam Husain

I keep my white coat white. I’m talking Mr. Clean White. Sensodyne White. White on rice White. New Balance sneakers on a middle-aged suburban dad White.

In fact, my doctoring group makes fun of me for getting my white coat dry cleaned, but I what can I say, it’s my favorite piece of clothing. And although we all have one, all of ours are a little different.

I doubt I will ever change where I keep my pen. Or my conveniently sized WhiteCoat clipboard. Or my stethoscope. Or my spare pen for when a patient asks to borrow one. Or even those two pins we got during the White Coat Ceremony 1…which, I should probably do something with someday.

I have practiced and prepared in this coat. It will do me well, even beyond the SimCenter. No matter how much we complain, we have to admit that Doctoring has taught us invaluable lessons. Now, on the brink of third year, it is hard to picture myself two years ago…wiping my sweaty palms on my new, pleated dress pants before shaking the SPs hand. I have come a long way. We all have.

Every time we put on that Temple white coat, we are ready:

we are ready to learn, we are ready to teach, we are ready to make a difference. But, we are also ready to make mistakes. And that’s okay. This year we are likely to be the most inexperienced members of the healthcare team. And just as these last two years have flown by, so too will the next two. Regardless of the impending challenges, we are ready for what’s next.

I, for one, will go from wearing my “white” white coat about once a week to almost every day. Naturally, I doubt I will be able to maintain this bleached white color. However, there is also pride in wearing an “aged” white coat. Every stain, every scuff, and every accidental pen mark will forever be linked to a memory. After all, a white coat is not meant to spend its life hanging in a locker.

This coat will travel with me across the street, and even across the state. And no matter how worn it gets, one thing will never change: this will always be my first white coat… And regardless of how “un-white” it may get, it will always be my favorite.

Katya Ahr and her niece, Chelsea

White Coat Reflection

Katya Ahr

I pull into the parking lot of my niece’s elementary school, nestled among tall pine trees. The weather is brisk, and it smells like camp. I had forgotten how long it stays chilly in the mountains despite all the early summer sunshine. I look out across the field she plays in everyday to the Adirondacks, close enough to touch but still blue-green in a cloudless June sky. I feel that little tug in my stomach I get every time I leave home and scold myself for ever forgetting how beautiful it is here.

I carry my white coat until I’m at the door of Chelsea’s classroom so I don’t look pretentious. I feel silly putting on my stethoscope, but then I catch her eye through the window and a smile explodes across her face. I see her squirming in her seat until her teacher lets her go, and she sprints across the classroom to let me in. I pry myself free from her little arms and she walks me to a big chair in the front of the room and sits down next to me to face her class. She is seven years old and tells everyone she meets that she wants to be a doctor when she grows up, just like Aunt Kat. My sister asked me to visit her classroom because Chelsea wouldn’t stop asking her if I could. I caved and made the 5 hour drive up from Philadelphia because Chelsea wrote a letter for career day about becoming a doctor like me so she could save kids with broken hearts like her little brother.

I field questions from the kids about how long I’ve been in school, what sorts of things I learn, what I do in the hospital. I tell them I read all the time, learn about the human body, and spend more time in the library than in the hospital. They ask me what kind of doctor I want to be. I hesitate to say that I want to treat cancer, but my niece says it for me. She is braver than I am. She is seven years old and has watched her little brother almost die five times.

Chelsea explains to the class that her brother was born with half a heart, got rushed into surgery straight out of their mom’s belly, and needed two more surgeries to try and fix it. She talks about the cooling vest he wears in the summer, the oxygen mask he wears in the winter, what happens when his oxygen gets too low and he turns blue, about spending weeks in Boston at the Ronald McDonald house. I look over at her, clear eyed and fiery, full of facts about the intimate workings of a hospital, an ICU, her brother’s heart. I want to take off my white coat and wrap her in it, carry her through elementary and middle and high school in this tiny town on top of a mountain in the middle of nowhere, through college, through medical school, through residency, hand her a scalpel and tell her to go, show everyone how big her dream is, save all the little boys born with half their hearts missing!

Instead, I look around me at the classroom full of tiny bodies from low income families talking about going to college. I hold my cynicism in my hands and place them in the pockets of my white coat. I take a deep breath. I look at Chelsea’s face, stoic and preternaturally sentient for a child, as it usually is. “I did this,” I think. “I was given this coat. It took me six years longer than everyone around me, but I am here and I am learning.”

Ernestina F. Gambrah

Raising the Ceiling

Ernestina F. Gambrah

There is a lot of pressure that comes with donning the white coat. There is an expectation that you are somehow superior, not in personhood, although some may take theirs to mean just that, or even in intellect, but rather you have some sort of superior knowledge of medical things and also a knowledge of the art of healing. When you wear the white coat, you are expected to be able to assess, diagnose, treat and empathize with those you interact with. You are expected to have an understanding of the complexities of patients physiological AND emotional processes. Sometimes it feels as though you are expected to be perfect. This expectation hangs heavy over my head at times when I wear the white coat. At times its sleeves are stiff; its waist band is unyielding towards my desire for a life that is bursting at the seams with happiness. It demands all my time, money, skill and emotion; choking me with its proverbial collar. Still, wearing the white coat is a reminder of the commitment I have made. That is, to dedicate myself to improving the lives of others. It allows me the privilege of taking part in the most intimate moments of patients’ lives. The white coat, even with all its pressures on me, brings a sense of comfort and pride to patients who look like me. It reassures little girls and boys with brown skin and kinky hair that they don’t have to just be one thing. The possibilities for them should be endless, but the truth is that for most they are not. Wearing the white coat allows me to step into rooms and occupy spaces to in effect, raise the ceiling for the next generation. And this makes it all worthwhile.

Sally Chen

One for Generations

Sally Chen

For as long as I can remember, my grandfather has always wanted one of his children or grandchildren to become a doctor. As a schoolteacher himself, he has always emphasized the importance of education and instilled those ideals onto his children, all of whom pursued college and graduate studies in respectable careers of their choice. However, as a man born in the early 1900s, to my grandfather, being a physician has always been one of the highest honors and most reputable careers that one can pursue. Since his children did not fulfill his lifelong dream, that burden soon fell onto my sister and me, and growing up, we were gently urged to consider a career of medicine. My ultimate choice to become a physician was my own careful, pointed decision, but my grandfather’s influence on my path toward medicine is undeniable.

I remember when I first announced to my grandfather that I would be attending medical school in the fall of 2017, he gently took my hand into his and lightly tapped the back of my hand a few times, as if giving me a nod and sense of approval. He’s always been a stern man of few words, but in that moment, his eyes twinkled, and the corners of his mouth rose into a smile as he congratulated me on my achievements so far, and of course, not forgetting to add that I had to keep working hard. He told me the story about how his father, my great-grandfather, had always wanted someone his family to become a medical doctor, and since his father had passed away before those wishes could be realized, my grandfather felt that, as the eldest child and son in the family, he needed to carry on his father’s wishes.

In wearing a white coat, I am learning everyday how I can be a better listener, a better caregiver, and a better diagnostician. My white coat carries a symbol of hope for my patients, a belief that I am here to make things better and everything will be okay. But in addition to the many strangers whom I will one day call my patients, my white coat, first, carries a sense of honor and success for the last three generations of my family. To my parents and older sister who have and continue to support me along this journey, to my grandparents who instilled a set of moral values and educational principles, and to my great-grandfather whom I’ve never had the pleasure of meeting, this one is for you.

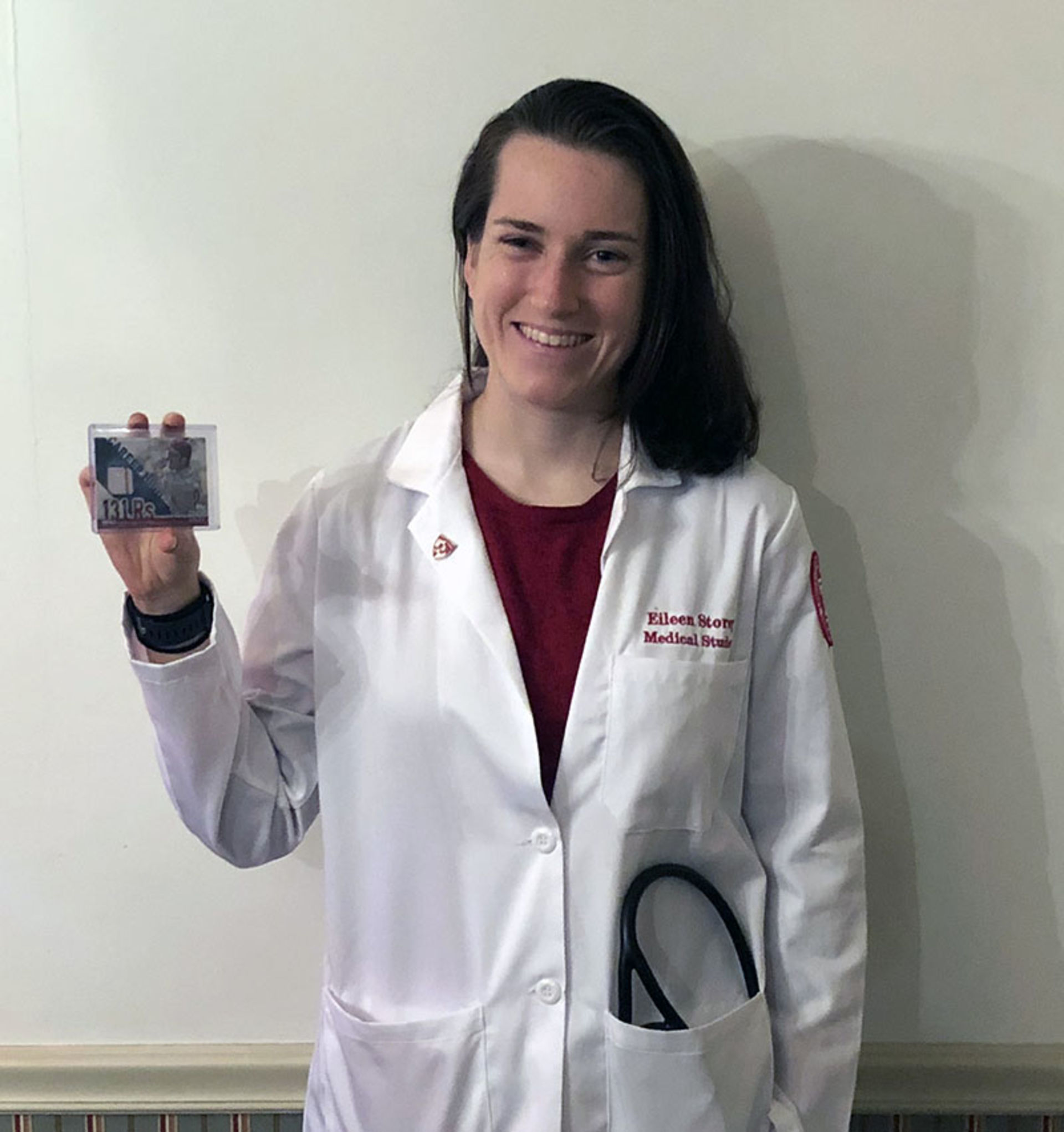

Eileen Storey

White Coat Reflection

Eileen Storey

I never liked wearing white. It stands out and it hides nothing. I also never liked wearing clothes that I have to iron.

My white coat rests in the back corner of my closet, tucked away with the other clothes I don’t like to wear. It seems an appropriate place for it because I don’t feel ready to wear it — or, at least, not ready to wear it without visible sweat stains giving away my insecurity. Maybe if the coat weren’t white?

Every Wednesday morning before I leave for Doctoring, I move aside a few (okay, many) Phillies shirts in order to reach it.

I check the pockets. In one, my reflex hammer and stethoscope. In the other, a small red notebook filled with blank pages that I haven’t yet had a reason to fill. I maneuver around the red notebook and feel the edges of the Chase Utley card I carry with me — a reminder about the privilege of working hard at work worth doing.

I pull the white coat on. It’s too big. I am still growing into it. Some days, I worry, not fast enough.

I think about my grandfather and my parents. The path they laid down in medicine. The freedom they gave me to find the same path on my own. I think about all that they know, and I remember how far I still have to go.

I think about how medicine is a field where I will never be good enough to stop learning, stop caring, stop trying. I love knowing that I can never outgrow it.

I look down and notice that I have dripped coffee on the front of my white coat. I remember how much I hate wearing white.

• • •

Michael Vitez, winner of the 1997 Pulitzer Prize for Explanatory Journalism at The Philadelphia Inquirer, is the director of narrative medicine at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University. Michael.vitez@temple.edu