What does compassion look like?

Stories from inside the examination room.

By Michael Vitez | February 20, 2017

Dr. David O’Gurek was explaining his next patient to the medical student accompanying him that day.

“This is sort of her last straw because she’s been here multiple, multiple times with urines that continue to show heroin,” said O’Gurek, who runs a Suboxone treatment program in Temple University Hospital’s Family Medicine clinic.

“I’ve let it go,” he continued. “It should be two and they’re done but I’m incredibly soft. Because I want them to do well. I also know what she’s up against. But today is the last chance.”

Heather, 24, waited in the exam room. Her blonde hair was in a bun. She was wearing jeans, black boots, and a grey hooded sweatshirt. She was anxious. She knew Dr. O’Gurek had given her more chances than she deserved.

She kept looking down at her index finger, the last knuckle and fingernail were missing, amputated five weeks earlier. The surgeon was supposed to have removed the stitches that afternoon, but Heather’s appointment with O’Gurek was more important. She pulled out the stitches herself the previous day.

O’Gurek tested her urine sample. Then he walked into the exam room, sat on the stool, wheeled up close to her.

If not for the stethoscope around his neck, there was nothing in his appearance to convey formality or that he was a physician. At 34, with a trim beard, he was wearing a plaid dress shirt, blue crew neck sweater, and tan khakis but no white coat. He thinks it puts distance between him and his patients.

“How are you?” he asked.

“Good. How are you?”

“Everybody’s frantic that you took your own stitches out,” he said.

She laughed. He examined the finger.

“It looks fine.” Then he looked up at her, and added almost admiringly, “It looks really good.”

***

Heather grew up outside Reading. Her mother struggled with substance abuse and went to jail when Heather was six.

She was raised by her father, but moved out at 17.

Heather decided at 22 to move to Philly and live with her mother, who has been in recovery for nine years, works in a mental health center, and mentors others fighting addiction.

Heather is a certified nursing assistant. She loves working with the elderly. Soon after she moved to Philly, she had a job interview at Temple Hospital.

She arrived early, so decided to get her nails done.

As she was crossing Broad Street, at Erie Avenue, a driver stopped and waived her across. The car behind swerved around the first car and ran over Heather’s leg.

She came for an interview, and ended up a patient. She couldn’t walk for months.

After the accident, she bought Percocet, a prescription narcotic, on the street, then moved on to heroin, which was cheaper.

When she started injecting into her jugular vein, her mother forced her into a seven-day rehab and then a methadone clinic.

Heather took the bus every day from their row house in North Philly to the methadone clinic in West Philly. Her urine tests at the methadone clinic began to show benzodiazepines, depressants, like Xanax. Fearing another addiction, the methadone clinic demanded Heather go to an inpatient rehab.

Heather went crazy the night before, buying bundles of heroin and Xanax with birthday money.

“It was stupid, so stupid,” she said.

“As a lot of patients do the night before rehab,” O’Gurek told the medical student, “Heather decided to go on a bender and injected into her left wrist what she thought was heroin and ended up being rat poison and developed compartment syndrome of her left hand. She had to be filleted open and developed dry gangrene on one of her digits that had to be amputated.”

After the amputation, she resumed going to the methadone clinic in West Philadelphia. A few days later, city bus drivers went on strike, and Heather felt four miles was too far to walk. She started using heroin again. In a panic, Heather’s mother called O’Gurek, who interceded on a Sunday to get Heather into his Suboxone program.

Suboxone, a newer treatment, quiets all the addiction receptors, so there is no physical craving, and no symptoms of withdrawal. One could take it for years, for life.

But switching was hard. Heather missed the instant kick of methadone. She was traumatized by her finger. She was fighting with her mother.

So even though she was taking her Suboxone, she used heroin and other drugs for weeks. Against the program rules. But on this visit she was hopeful. She’d finally stopped the other drugs.

***

O’Gurek let go of her hand.

“So how are you?” he asked again.

“A lot better.”

“What’s that mean?” His voice was soft, sincere, and filled with inflection and warmth, a tool of his trade if ever there was one. How he spoke conveyed as much as what he said.

“I haven’t used. I’m happier. Me and my mom doing a lot, lot better.”

“What’s the difference you think?”

“I’m more positive. I’m going to my meetings. And speaking and talking about how I feel. And my friend that I got in contact with. She was my best friend for years and years. Like my only female best friend. I finally got in contact with her…We’ve been talking more.”

In the exam room across the hall, which is smaller, O’Gurek, also an assistant professor of family and community medicine at Temple’s Lewis Katz School of Medicine, often gives the medical student the stool and he will pull out the footrest on the examination table and sit on that, making the patient interview feel even more like an informal conversation.

He understands that listening, caring, may be the most important medicine he provides.

“The relationship with people is the miracle drug,” he said, “for patients and for doctors.”

O’Gurek also feels for too long those struggling with substance use disorders have been judged more harshly, “not just in society but by medicine.” With 20 million Americans wrestling with substance abuse, 78 dying every day from overdose, the country is beginning to accept addiction as an illness, he says, not a moral failing.

“Yesterday was tough for me,” Heather continued, explaining that someone else close to her “….was really, really high. I didn’t know whether to call the ambulance or what.”

After listening to her for a while, as Heather shared the details of the previous day’s event and her life, O’Gurek said to her, “You’re different.”

“What do you mean?” Heather asked.

“You’re you. Just even the way you’re talking and the things you’re saying and the way you’re approaching things.”

“Is that good?”

“Yeah.”

“You were making excuses before. And you’re not talking like that at all now. And you look clear. It’s not only that your thoughts are clear but you look clear.”

It was also clear from his tone and his positive comments that Heather’s urine was clean. He never actually told her because he didn’t need to.

“So what’s going on with you and your mom?” O’Gurek asked.

“I think she knows I’m trying harder.”

“Let’s check in next week,” he concluded. “Stay on track. Keep up the good work. Are you happy?”

“Um-hmm.”

“That didn’t look convincing,” he said.

She laughed. “No, I’m happy….I just don’t want to jinx everything.”

“Right. Don’t get cocky. Just keep doing what you’re doing. One day at time. One step at a time. Sometimes that stuff seems so dumb. But honestly, all any of us can do is one day at a time.”

He rolled back to the computer, spent a few minutes at the keyboard.

She went across the street to the hospital pharmacy to fill her prescription for another week of Suboxone.

Before going in to see his next patient, O’Gurek paused in the hallway, turned to the medical student with him and said, “This is why I give them more chances than I should.”

***

O’Gurek grew up in small tight-knit town, Summit Hill, PA near Jim Thorpe. He was taught “the values of my parents. Fight for what you believe in, fight for the underdog.”

He remembers being in medical school at Penn State and going to a student-run clinic In Harrisburg, next to a homeless shelter. He was struck by the gratitude of patients, the sense of ownership, these are our doctors. “The men in the homeless shelter walked us to our cars at night,” O’Gurek recalled.

He has never forgotten the feeling he had, that they had, the importance of serving this community, the dignity of his patients.

He has hard days. Twice in one afternoon recently he had to cut patients from his Suboxone program. “You could see it broke his heart,” said a medical student who was with him. Not only was their urine dirty, again, but they lied about using.

One of his regular clinic patients, not an addict, came to see him recently. She suffered from mental health issues but was doing better. They had a good visit. A week prior to her follow-up visit, on the news, he saw she had been murdered by her boyfriend. He felt grief, despair, doubt.

“On the hamster wheel of medicine, does any of it really matter? You ask yourself that,” he says. “Those are the low moments. And it is the relationships that bring you back, that keep you coming back.”

“I realize we can’t be everything to everyone,” he says. “I realized that very quickly or you do burn out. There are wins. There are losses. You have to celebrate the small wins.”

***

This was a small win.

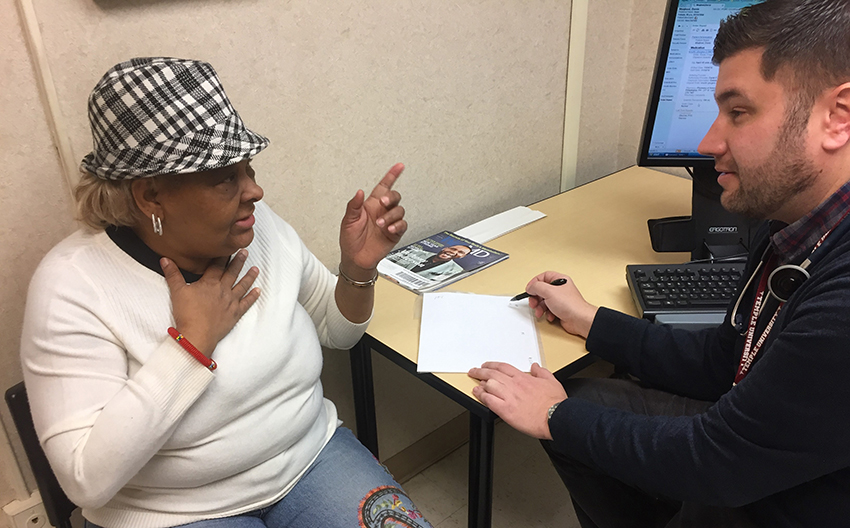

O’Gurek opened the door to the examination room. Dorris Lemon-Maqbool, 66, had a skin lesion on her chest that he would need to cut off. He knew she would be apprehensive, and the rapport was evident from his first words.

“You’re always so coordinated,” he said to his patient. “Look at the hat and the boots.”

“I ain’t old yet,” she replied.

“Did I say anything about being old?”

“I’m just letting you know,” she said. “Just letting you know. Thank you for the compliment.”

She indeed was wearing a furry hat and furry boots that matched.

She had been his patient in the Temple Family Medicine clinic for three years. The lesion was a little blood vessel tumor, resembling a tiny inchworm, that popped through her skin and often bled. He would numb her with an injection and then cut away the growth.

“Can I have you sit up here,” he said. “I think were’ going to get rid of this once and for all…..”

“Oh boy,” she said, as he helped her to the examination table. “This is fear. I’ve been trying to psych myself up not to be scared.”

“Well, we know you don’t like needles,” he said. “You want to sit up or lay down. However you’re more comfortable.”

O’Gurek paused a moment, studying the wound.

“We might need a suture.”

“Don’t say that. I don’t want no string hanging out.”

“What? You’re going to wear a low cut shirt?”

“It’s Christmas. I don’t want to look like a Raggedy Ann patched up.”

This was the second time she was having this procedure. O’Gurek let a student do it before, but apparently she didn’t cut the root and the lesion grew back.

He was ready to begin.

“Oh god I don’t want to see that needle. Oh my god.”

She nervously continued talking to the medical student in the room. “I got a good doctor. I wouldn’t trade him for anything in the world. You are working with a terrific man.”

“You’re just being nice because of what you did last time,” O’Gurek said to her.

“What I do?” she asked.

“I had a student come in last time, and you said, `Oh my gosh look at how handsome my doctor is.’ You never say that about me.”

She laughed.

“Are you ready?” he asked.

“No.”

“Keep your eyes closed.”

“You got it.”

He injected her.

“Mmmmmm. Mmmmmmmmm. Oh my god.”

“You ok?”

Silence as he continued to numb the site.

“You doing all right?”

“Umm hmm.”

“You feeling me poking you?”

“Not now.”

With a scalpel, he worked. She told him about her trips to the casinos.

“Do you have to do a biopsy?” she asked.

“Yeah. We did the last time, the blood vessel from the pyogenic granuloma.”

“Oh, like I know that big word.”

“Well you asked, didn’t you? Basically a blood vessel tumor.”

“Ok. I can deal with that. That medical term takes me out.”

Soon he was done. No stitch after all. He apologized for having to use a plain Band-Aid to cover it instead of something more stylish.

He helped her down.

“You going to your mom’s for Christmas?” she asked.

“Yes,” he said.

“Make your mom happy.”